The racing life and times of Jerry Grant

Part six –1973 season

USAC opened

the 1973 race season embroiled in another dispute with the Automobile

Competition Committee for the United States (ACCUS) the umbrella organization

of United States auto racing sanctioning bodies to the Fédération

Internationale de l'Automobile (FIA). USAC’s complaint was about the number of

“Full International” events set aside for the other ACCUS members. The

increasing number of “Full International” races eroded USAC’s control over its

drivers and led to USAC’s threat to withdraw from ACCUS in 1974

Specifically,

the USAC organization was irritated over the number of Sports Car Club of

America (SCCA) events classified as “Full International,” which enabled drivers

from ACCUS one club that held an FIA license to freely race with another ACCUS

club. The entire 1973 SCCA L&M

Continental Series was classified as ‘Full International” if that event was

listed as “Full International."

USAC then

decided to refuse to allow driver interchange between USAC and SCCA during 1973,

which led to Jerry Grant and Mark Donohue not renewing their USAC licenses, and

in effect resigning from the USAC. In his April letter to USAC, Grant pointed

out that he only had a ride for the three USAC “Crown Jewel” 500-mile races,

and he had chances to race elsewhere and get paid.

Jerry Grant

planned to compete in the opening round of the SCCA L&M Continental Series

formula car series race at Riverside for car owners Chuck Jones and Jerry

Eisert. Although it was one race deal, Dan Gurney and Grant planned to compete

in the 1974 L&M series with a new All American Racing (AAR) Eagle creation.

Mark Donohue

was scheduled to compete in the entire 1973 SCCA Canadian-American (Can-Am)

Challenge series in the Penske Porsche turbocharged 917-10. Grant’s and

Donohue’s resignation meant they could still race in the USAC FIA

internationally-sanctioned 500-mile races at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway

and Ontario Motor Speedway. Despite the negative

publicity generated by the defending Indianapolis ‘500’ winner, Donohue, and

the first man to turn a lap at 200 MPH in a USAC championship car, Grant,

quitting the organization, USAC officials remained intransigent.

Photo of Jerry Grant in 1973 courtesy INDYCAR

Grant was

entered for the 1973 Indianapolis ‘500’ as the driver of Oscar ‘Ozzie” Olson’s

#48 “Olsonite Eagle” as a teammate to Bobby Unser, with a third Eagle entered

with no driver named. Practice at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway opened early

on April 28, but Grant was at Riverside International Raceway in California for

the L & M SCCA Formula 5000 race on April 29th.

Grant

qualified ninth at Riverside but suffered unspecified mechanical problems during

his qualifying heat but he still started the feature on a sponsor’s

provisional. Grant’s ‘KBIG’ Lola T330 then fell out of the feature race after

nine laps when the 475-horsepower Chevrolet V8 engine overheated and Jerry

finished in the 24th position.

On May 12,

for the second year in a row practice prior to the first day of Indianapolis

‘500’ qualifying brought tragedy to an Eagle driver. Art Pollard in Bob

Fletcher’s ‘Cobre Firestone Special’ customer Eagle crashed in the south short

chute during morning warm-ups and Art died an hour later at Methodist Hospital.

Grant was the

third car out on track from trials and qualified his white #48 car with orange

and blue trim for his seventh Indianapolis 500 start with an average of 190.235

MPH, which would place him on the outside of the sixth row in the field of 33

cars. As time trials progressed, Bobby

Unser saw his year-old track one and four-lap track records smashed but he

qualified his Olsonite Eagle in the second starting position behind Johnny

Rutherford. Before qualifying was completed, the third Olsonite Eagle driven by

Wally Dallenbach made the starting field.

Race Day,

Monday May 28 1973 dawned cloudy and cool with showers that delayed the

scheduled start over four hours. As the

field of 33 cars accelerated and took the green flag from starter Pat Vidan,

the McLaren of David “Salt” Walther who started alongside Grant in the middle

of the sixth row, climbed the left front wheel of Grant’s Eagle. Walther’s car pin

wheeled in the air over the top of Dallenbach’s Eagle and flew into the outer

catch fencing.

Two of the

support posts of the catch fencing were torn out as the front of Walther’s car was

sheared off and burning methanol fuel and parts flew into the trackside folding

chair seating area located just a few feet away. With a total of ten cars

involved in the horrific crash, starter Vidan immediately displayed the red

flag to stop the race.

Salt Walther

suffered third-degree burns over 25% of his body and nine spectators were

hospitalized, two in critical condition. Before the clean-up of debris and

track repairs could be completed, it began to rain again. The 1973 Indianapolis

500-mile race would completely restart on Tuesday May 29.

Overnight,

all the damaged cars except Walther’s were repaired. On Tuesday morning it

rained again which delayed the scheduled 9 AM start. During the delay there

reportedly there was a stormy drivers meeting during which several drivers

criticized race officials for the decisions which the drivers claimed led to

the previous day’s conflagration.

After the

track dried, the cars were started again to another start, but at the beginning

of the second parade lap, John Martin in his own unsponsored McLaren pulled

into the pit area and signaled to officials that it was raining on the course. Soon

after, heavy showers settled in and by 2 PM, officials announced that the start

of the 500-mile race was moved to 9 AM Wednesday morning.

The small

crowd present at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway on Wednesday saw a clean start

as Bobby Unser in his Olsonite Eagle took the lead and held on for the first 39

laps, while many of his expected competitors, including AJ Foyt, Mario

Andretti, Lloyd Ruby, and Peter Revson retired. On lap 48, the #62 Olsonite

Eagle of Dallenbach retired with a broken connecting rod in its Offenhauser

engine.

The red flag

was again displayed on lap 57 due to Swede Savage’s horrific crash on the main

straightaway, and during the delay, a clearly unnerved Jerry Grant was

interviewed by ABC Sports. Grant, who had brought his Eagle to a stop just

short of the Savage accident debris field, complained that he needed to run a

different line to avoid driving through the oil on the track. Grant responded

to the interviewer’s follow-up question about the safety of the track by replying “it’s making an old man out of me.” Not

surprisingly, Bobby Unser interviewed moments later by ABC Sports refused to

agree with Grant’s assessment of track conditions.

After one

hour and ten minutes the race resumed. Grant’s Olsonite Eagle retired with the

same malady as Dallenbach’s, a broken connecting rod on lap 77, and then Bobby Unser

made it a hat trick when his car’s Offenhauser engine broke one of its four

connecting rods at the halfway point. Mechanical attrition in 1973 ‘500’ was

extremely high with just twelve cars still running with several of those cars

more than seven laps down, when showers began to fall on the leader’s 129th

lap.

When the rain

intensified the race was stopped with the 1973 500-mile race’s fourth and final

red flag on lap 133 with Gordon Johncock in the lead. Moments later Johncock was declared the

joyless winner of the 1973 Indianapolis ‘500.’

There was no Victory Banquet held, and though preliminary results listed

Grant in seventeenth place, he was credited with a nineteenth place finish in

the final official results and earned $16,675.

The public

fallout from the circumstances of the 1973 Indianapolis 500-mile race, with the

senseless death of pit worker Armando Teran, the injuries to nine spectators

and the critical burns to two drivers (one of whom, Swede Savage would later

die) was immediate.

STP Corporation President Andy Granatelli the sponsor of

Savage’s and Johncock’s Eagles, stated that “all of us in racing must face the

fact that we are simply going faster than our tracks and drivers can safely

handle these flying missiles.” If changes were made promptly, Granatelli

threatened to pull out of racing "This is not a demand for reform, but a

sincere and sad plea to all of my fellow members of the racing community to

assist me in obtaining this kind of reform," Granatelli said.

On Saturday

June 2 1973, the USAC Board of Directors met in a special emergency session,

and the Rules Committee and the Board quickly voted to make immediate rules

changes. The allowable width of the rear wing on the championship cars was

reduced from 64 inches to 55 inches. The allowable fuel capacity of all cars

was slashed from 75 gallons to 40 gallons, with fuel bladders only allowed to

be installed on the left side of the cars. To further reduce speeds, the total

amount of fuel allotted for a 500-mile race was reduced from 375 gallons to 340

gallons.

Jerry Grant

did not race again on the 1973 USAC championship trail until late August at the

Ontario Motor Speedway for the fourth annual ‘California 500.’ In one year, the atmosphere at Ontario had

changed dramatically, as the track was under new management but there were

still serious long-term financial concerns.

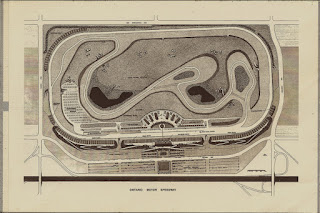

Originally

envisioned in 1963, with ground broken in September 1968, the Ontario Motor

Speedway was built at a total cost of $25.5 million. The completed project designed

by Benham-Kite and Associates and built in 22 months by the Stolte Company Inc.

featured a 2-1/2 mile oval modeled after the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, but

one lane (10 feet) wider, and more banking in the two short chutes with a flat

infield road course.

The track had a unique public funding structure: the track

owner, the Ontario Motor Speedway Corporation (OMS Corporation) was a

non-profit entity created and controlled by the City of Ontario to issue the

bonds for the purpose of raising the money required to purchase the 800 acres adjacent

to the San Bernardino Freeway (also known as the “10”) and construct the facility.

The Ontario

Motor Speedway Incorporated (OMS Inc.) a for-profit company initially headed

David Lockton and later by Ray Smartis, had a seven-year contract to oversee

the construction and operation of the Speedway. A 1968 Market Support and

Economic Evaluation Study by Economics Research Associates Inc. anticipated that

over one million persons would attend events at the Speedway each year. The $20,000

study concluded that with that level of attendance, the Speedway would easily

generate sufficient income for the track operator to pay the OMS Corporation

rent, which would be used service the 7.5% interest payments on the bonds.

A postcard drawing of the back side of the OMS main grandstand

The track

opened in 1970 with 140,000 permanent grandstand seats and a five-story control

tower building that featured a private “Victory Circle” VIP club with suites,

restaurants, bars, and air-conditioned seating. Membership to the “Victory

Circle Club” cost $250 annually and tickets to the inaugural California ‘500’

USAC race in 1970 ranged from $5 to $25. That first USAC race drew 178,000

fans, but then attendance dropped to a reported 130,000 for the 1972 running of

the California ‘500.’

On November 29

1972, after just over two years of operation, the Ontario track was padlocked

because the operator, OMS Inc. failed to make the annual rent payment of $2

million to the OMS Corporation to be used to cover the interest payments to

bondholders. OMS Inc. claimed that it was impossible to pay the $2 million

annual rent, which it said represented 60% of the Speedway’s annual gross

revenue.

The track

operator, OMS Inc., reported that it lost over $9.7 million since the track

opened and took the position that the bondholders should accept a percentage of

profits, rather than a fixed payment.

The OMS Inc. counter-proposal was rejected, and with the Speedway operator

in default, the original agreement was terminated in December and the OMS Corporation

began a search for a new track operator.

After a

couple months of negotiation, a potential savior was identified - Western

Racing Associates (WRA), which had offered a proposal to run the Speedway in

1968 agreed to lease the Speedway for 12 months. Allegedly backed by razor

fortune heir William Gillette, the publicly identified officials of the company

were Conrad Sprenger, the president of an Ontario radio station, Orange County

contractor/developer Kent B. Rogers and as a recent addition to the group,

former OMS Inc. general manager Ray Smartis.

On Thursday

January 4 1973, the five-member governing board of the OMS Corporation unanimously

accepted the WRA proposal. However, a few days later just before the deal was

set to be signed, WRA backed out of the deal. The Speedway remained shuttered

as the OMS Corporation was forced to renew its search for a new track operator.

For this third search round there were three leading groups in competition to

run Ontario Motor Speedway. One group headed by Ray Smartis, another group was

a reportedly a coalition of local labor unions, and then there was the Ontario

Motor Speedway Operation Company Limited (OMSOC).

The

principals of OMSOC were racing industry heavyweights- Anton Hulman and the

Indianapolis Motor Speedway Corporation, 1963 Indianapolis ‘500’ winner and USAC

racing team owner Parnelli Jones, Jones’ racing team partner and Southern

California car dealer Vel Miletich, Jones and Miletich’s public

relations/business manager Jim Cook, and the pair’s lawyer a man named Dudley

Gray.

Other

partners in the OMSOC included Peter Firestone, grandson of Firestone Tire and

Rubber Company founder Harvey Firestone, Mike Slater the president of Commander

Motor Homes and a USAC car owner, and Arthur D Hale, the founder and president of

US Mag Wheels. Parnelli Jones was President and Vice-Chairman of the group,

while Tony Hulman, who held the majority of the shares, was OMSOC Chairman. Gray was the General Counsel, Miletich the group’s

Secretary-Treasurer. IMS President and long-time Hulman confidant Joseph

Cloutier was a Vice-President with Jim Cook named the OMSOC General Manager.

OMSOC quickly

emerged as the frontrunner, but before the OMSOC proposal was submitted, some

tough behind the scenes negotiating was done with USAC. After weeks of

conferences between the IMS Corporation and USAC, a deal was finally signed at

the first USAC race of the year at Bryan Texas. USAC agreed to sanction the

1973 California ‘500’ for a $500,000 combined sanctioning fee and purse, which was

a reduction of $200,000 from 1972.

At the April

10 deadline, OMSOC submitted its proposal, which called for the group for the

group to immediately pay all the outstanding debts incurred by OMS Inc., and

pay the OMS Corporation $150,000 in rent at the end of the first year on March

31, 1974. OMSOC would pay $200,000 rent for the second year, $250,000 at the

end of the third year, $400,000 for the fourth year and $512,000 the fifth

year.

To supplement

the sharply reduced rent payment amounts, OMSOC would also pay the OMS

Corporation a 50% share of the Speedway profits. The two other competing groups

which had submitted proposals withdrew their proposals after the details of the

OMSOC proposal were revealed.

The OMSOC

offer was unanimously accepted by the OMS Corporation Board, and after the

signing the one year agreement with a five-year option, OMSOC President

Parnelli Jones accepted the keys to the plant on April 22 1973. “We have a year

to find out if the track can be operated successfully," Jones said at the

signing. "We honestly don't know yet. We do know that it will take all the

cooperation of the community, the drivers, car owners, manufacturers, racing

fans, and sanctioning bodies to make it happen."

Planning for

the fourth annual 1973 California ‘500’ began immediately, with changes in the

format from the previous three years. Qualifying would be just two laps, not

four laps and the day after qualifying there would be two 100-mile “qualifying

heats” held with the finishing order of the races to set the 33-car field

behind the front row.

The shorter “qualifying

heats” would not pay individual purses but would award USAC championship points.

USAC formally issued the sanctioning agreement for the 1973 “California 500” on

April 20, 1973. OMSOC announced for the

first time at Ontario, camper parking would be allowed in the infield, which

would not create sightline problems as the backstretch at Ontario was several

feet higher in elevation than the front straightaway.

During

practice for the 1973 “California 500” Jerry Grant and the ‘Olsonite Eagle #48

turned in a practice lap speed of 190.645 MPH which put him near the top of the

speed charts. After qualifying was completed on August 25, the same three

drivers made up the front row of the starting grid for the 1973 “California

500” as the 1972 race; Grant, Peter Revson and Gordon Johncock.

But unlike

1972, Grant did not win the pole position as he qualified second fastest with a

two-lap average of 198.873 MPH, while pole-sitter Revson broke the magic 200

MPH barrier, but did not approach Bobby Unser’s year-old track record with a

two-lap average of 200.089 MPH.

Grant,

Revson, Bobby Unser, Jerry Karl in Smokey Yunick’s turbocharged Chevrolet-powered

Eagle, AJ Foyt and Foyt’s teammate

George Snider chose to save the wear and tear on their equipment and did not race

in either of the twin 100-mile “qualifying heat” races on run August 26. Technically,

Grant, Johncock, and Revson by qualifying on the front row were not required to

run either 100-mile races.

The twin

40-lap races were won by Johnny Rutherford and Wally Dallenbach, so they would

start in fourth and fifth positions respectively for the 500-mile race on

Sunday September 2. The day before the California ‘500,’ a group of car owners

met in a closed-door session to discuss what was described as “upgrading the

design, performance, safety, and finances of the USAC championship circuit” while

at the same time a closed-door drivers meeting was held.

The next day,

Grant’s #48 Olsonite Eagle was the first car out of the California ‘500,’ for

the second year in a row, as he crashed in the second turn on lap two after

second place driver Gordon Johncock’s “STP Double Oil Filter” Eagle blew its

Offenhauser engine and laid a slick mixture of oil and STP Oil Treatment on the

track surface.

Dallenbach,

the eventual California ‘500’ winner was behind Grant and while his “STP Oil

Treatment” Eagle also slid in the oil, Dallenbach somehow saved it from

crashing. Johncock’s crippled Eagle

coasted around to his pit area and by crossing the start/finish line; Gordon

was credited with a 32nd place finish. Jerry Grant in last place earned just $2,305

out of the total purse of $370,000.

Grant tested

the early development Formula 5000 Eagles in late 1973, and while AAR built

Eagle chassis for the 1974 and 1975 SCCA/USAC Formula 500 championships seasons,

Jerry Grant was not the AAR team’s driver. After the 1973 “California 500,”

Grant never drove again for All American Racers Inc., although he drove nothing

but Eagles for the rest of his USAC racing career.

Postscript

– the USAC/SCCA battle resolved (for awhile)

Author's copy of an SCCA/USAC F5000 program

USAC’s

threatened 1974 withdrawal from ACCUS over the “Full International” status of

SCCA races never occurred. Instead a series of meetings between USAC and SCCA

officials commenced in January 1974 with an agreement was reached in May 1974

for the Formula 5000 series to be jointly sanctioned by the SCCA and USAC. The

eighth season of the open wheel formula car road racing series, known as the

1974 “SCCA/USAC Formula 5000 Championship” began June 2 at the Mid-Ohio Sports

Car Course with "Buckeye Cup."

Beginning immediately,

the Formula 5000 championship was open to not only SCCA legal cars but also to

USAC cars powered by either 161 cubic inch turbocharged, 255 cubic-inch double

overhead camshaft or 305 cubic inch "stock block" engines. The USAC

cars would run on methanol, with a required pit stop for turbocharged cars.

Over the next

few years, there were a number of USAC stars that competed in the Formula 5000

series; the roster included Mario Andretti, Mike Mosely Johnny Rutherford, as

well as Bobby and Al Unser, but there were only three turbocharged Offenhauser

powered entries that ever tried to run the Formula 5000 series.

In a press

release that announced the agreement worked out with USAC President Reynold

McDonald, SCCA President Cameron Argetsinger was quoted that “joint sanction is

an important step, but more importantly, USAC and the SCCA have agreed to

direct their best efforts of a long-range plan for a common open-wheel car and

engine formula and a single championship to be run on both road courses and

ovals.” The timetable called for the two groups to formulate a detailed plan for

approval by each governing board by January 1975 with the common formula put

into effect in January 1976.

Alas, this

plan never came to pass as the SCCA and USAC were unable to agree on a common

formula. Nearly a year after the planned target, on October 11 1976, the USAC

announced its withdrawal from the joint sanction of the Formula 5000 series. Frankie

DelRoy, USAC’s Technical Director told Milwaukee Journal writer Roger

Jaynes “for a while it looked like we could work out a common formula. But

every time we tried to work out a compromise the SCCA wanted everything their

way. Fuel, tire sizes, type of engine- everything.”

In the end,

said DelRoy, “it was a case of us helping out the SCCA and them not helping

us. They got our name drivers - Mario

Andretti, Al Unser and the rest to strengthen their series, but they didn’t

want to help us one bit.” The Formula 5000 series came to an end at the close of

the 1976 season, and most of the teams enclosed their Formula 5000 chassis in

full bodywork to compete in the “new” SCCA Can-Am series for 1977.

Postscript-

the slow death of the Ontario Motor Speedway

After

attendance dropped again for the 1973 “California 500,” the new operators, the Ontario

Motor Speedway Operation Company Limited (OMSOC) moved the 500-mile USAC race

date to March for 1974. The original one-year operation agreement between OMSOC

and OMS Corporation was renewed with amendments reducing the rent payments in 1974.

The March 9

1975 USAC California ‘500’ attracted just 52,000 spectators, and after the race

it was revealed that OMSOC owed $119,000 in back taxes, $7,000 in penalties and

$75,000 in rent due on March 31 1975. On March 27 1975 OMSOC President Parnelli

Jones president terminated the lease saying that OMSOC had lost too much money.

George Mim Mack, chairman of the non-profit OMS Corporation which issued the bonds was asked in a 1975 newspaper interview if the Ontario Motor Speedway would ever be profitable. His response was “you’d have to say since the first operators were knowledgeable and the current group is very knowledgeable that it may be unrealistic for that to happen in the immediate future.”

George Mim Mack, chairman of the non-profit OMS Corporation which issued the bonds was asked in a 1975 newspaper interview if the Ontario Motor Speedway would ever be profitable. His response was “you’d have to say since the first operators were knowledgeable and the current group is very knowledgeable that it may be unrealistic for that to happen in the immediate future.”

OMSOC closed

their offices on March 31, 1975 and the City of Ontario assigned ten City

employees to care for the facility with Ray Smartis returning as General

Manager later in 1975. Smartis moved the 1976 California ‘500’ date back to

Labor Day, and the Ontario Motor Speedway continued to struggle along as it

hosted Spring and Fall USAC race dates beginning in 1977 but it still lost

money. Beginning in 1978, the threat of foreclosure hung over the track daily

and that possibility had to be reflected in every contract for track use.

By 1980 the

latest management group was bankrupt, and Ontario Motor Speedway bonds were

nearly worthless, while the value of 800-acre property had skyrocketed. In

December 1980, the City of Ontario sold the bonds, and in effect the property

and facility, to the Chevron Land Management Company for $10 million. By February 1981 the track was deserted.

During 1981,

Chevron demolished the track facilities and in the summer of1986 moved the 1.5 million cubic yards of dirt that formed the earthen berms. With the last vestiges of the track Chevron developed the area for commercial

and residential uses.

There are no landmarks of the “Big O” left, although there is a multi-use public park in the City of Ontario California named in honor of the Speedway and several streets in the area of the park are named after automobiles such as Duesenberg Drive and Porsche Way.

There are no landmarks of the “Big O” left, although there is a multi-use public park in the City of Ontario California named in honor of the Speedway and several streets in the area of the park are named after automobiles such as Duesenberg Drive and Porsche Way.

In the next

installment of the Jerry Grant story in 1974, Grant moves onto another team as

a replacement for an injured colleague.