Two works by the

master - Emil Diedt

color photos by the author

black & white photos appear courtesy of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Collection in the IUPUI University Library Center of Digital Studies

During a recent visit to the World of Speed museum to view

the special Indianapolis ‘500’ exhibit, the author photographed two automotive

works of art built by one of the sport’s master metal craftsmen. Emil Diedt, born

in Germany in 1897 worked out of a shop in Culver City California and was best known as the builder of the

identical pair of 270-cubic inch Offenhauser powered front wheel drive cigar-shaped ‘Blue

Crown Spark Plug Specials’ owned by retired driver Lou Moore, but Diedt built two more similar cars later.

Reputedly the advantage of the front wheel drive at the Indianapolis

Motor Speedway was due to more weight centered over the driving wheels which helped

to “pull” the car through the corners and reduced the car’s tires sliding once

the track surface got slippery with oil during the race. This proved to be

correct, as front wheel drive cars led every lap of the 1947 500-mile race.

The new Blue Crown cars debuted at the 1947 Indianapolis

500-mile race, qualified in third and eighth positions and then dominated the

race, leading 177 laps. With 100 miles

to go and his cars running in first and second positions, Moore signaled to the

drivers of his cars via the pit board “EZY” the signal for the pair to take it

easy. With just eight laps to go the race leader 39-year old rookie Bill

Holland waved his teammate, Mauri Rose past him as Holland thought he held a one-lap

lead. Holland was mistaken and Rose

raced away to score his second (and first solo) Indianapolis victory as the angry

Holland finished 32 seconds behind Rose.

1949 '500' winner Bill Holland

In 1948, the ‘Blue Crowns’ repeated their domination, with

Rose and Holland again finishing one-two over two minutes ahead of the third

place finisher, the front wheel drive Novi driven by Dennis ‘Duke’ Nalon. In

1949, Holland finally won the ‘500’ as Mauri Rose’s car broke a magneto strap

while he ran in second place with eight laps to go. After a month of ongoing

disputes with car owner Moore, the outspoken Rose angrily quit the team, or was

fired, depending on whose version one chose to believe.

The Keck car

The immediate success of the Diedt-built front wheel drive

‘Blue Crowns’ led to other car owners looking for their own versions. One such

car owner was Southern Californian Howard B. Keck, heir to the Superior Oil

fortune. Keck earlier purchased John Balch’s Offenhauser powered midget racing

operation together with the services of co-chief mechanics Jim Travers and

Frank Coon and their friend fuel injection pioneer Stuart Hilborn. After

dominating in United Racing Association (URA) ‘red’ circuit for Offenhasuer

powered cars, the Keck team and was ready to conquer Indianapolis.

With Keck’s backing, Travers and Coon ordered a new front

wheel drive chassis from Emil Diedt for the 1948 Indianapolis ‘500.’

Indianapolis native son Jimmy Jackson who scored two top-five finishes in the 1946 and 1947 500-mile

races, qualified the new #61 ‘Howard Keck Special’ at 127.51 miles per hour

(MPH) for the fourth positon. After he started the race on the inside the

second row behind Rex Mays, Rose and Holland, Jackson ran just outside the top five for most

of the race, but his good finish was spoiled when a wheel spindle broke on the maroon colored machine with

six laps to go and he spun into the infield.

Jackson and the Keck team returned to Indianapolis in 1949; Jackson wanted to paint the car green but Keck refused so Jackson wore green gloves. The ground-breaking Hilborn fuel-injected ‘Howard Keck Special’ started seventh after Jackson qualified with a

four-lap average of 128.023 MPH. At the end of the 500-mile test, the #61 Diedt

front wheel drive machine finished sixth, seven minutes behind winner Hollard’s

similar machine.

Mauri Rose adds Pennzoil in this 1951 publicity shot

For the 1950 Indianapolis 500-mile race, former ‘Blue Crown’

pilot Rose was the new driver of the Keck/Offenhauser front wheel drive Diedt machine

and Mauri qualified with a four-lap

average of 132.319 MPH to start on the outside of the front row. Rose earned a

measure of revenge as he out-qualified both of the Moore ‘Blue Crowns;’ Holland

was tenth fastest and Rose’s replacement, Tony Bettenhausen timed in eighth

fastest.

Rose and the Keck entry led the race on three occasions for

a total of 15 laps, but Rose was slowed when he was briefly forced out of the

cockpit by a pit fire on his only stop on lap 109. Rose had pitted from the lead and once the fire was extinguished Mauri was back underway

and he recovered to finish third behind Holland in a controversial rain-shortened

138-lap race. The deluge lasted just 60 seconds, but Speedway officials stopped the race and initially scoring was very confused, with Rose originally unofficially scored in fifth place. The #31 Keck entry’s appearance in race footage of the 1950

Metro-Goldywn-Mayer film ‘To Please a Lady’ was little satisfaction for Rose who

lost his chance to become the first Indianapolis 4-time winner.

For the 1951 Indianapolis 500-mile race the Emil Diedt

bodywork was painted black with yellow and red trim and the #16 car carried

Pennzoil sponsorship. Mauri Rose, who turned 45 years old four days before the

race, qualified fifth fastest at 133.422 MPH to start from the middle of the

second of eleven rows of three. In his 15th Indianapolis ‘500’ on his 127th

lap, while Rose ran in third place, the right rear wire wheel of the ‘Pennzoil

Special’ collapsed. Rose fought for control as the car slid into the infield

off turn two and into a drainage ditch where it overturned and momentarily

trapped Mauri underneath.

The aftermath of the 1951 flip

Legend has it that Rose retired from racing on the spot, but

in actuality, it was the death of Rose’s first wife and mother of his two young

children Mauri Junior and Dory who both were polio survivors during the winter

of 1951 that lead Mauri to formally announce his retirement. On January 30 1952, from his home in Van Nuys California,

Rose told reporters that after 24 years, he could no longer risk his life

racing.

The 1951 Indianapolis ‘500’ marked the final race appearance

of the Howard Keck owned Emil Diedt front wheel drive machine, as the following

year the Keck team entered a 270-cubic inch Ferrari 375 and a new

Offenhauser-powered creation from Frank Kurtis known as the 500A but nicknamed the

“roadster.” The Diedt car as displayed at the Museum of Speed is expertly

restored as how the car appeared in the 1951 Indianapolis ‘500.’

Reputed Chicago suburban south side organized crime figure Carmine George “Babe”

Tuffanelli became interested in automobile racing and owned several beautifully maintained ‘big cars’ and midgets which raced in events

across the country. The team of cars, each fielded as ‘Tuffy’s Offy’ were

maintained by experienced mechanic Charles Pritchard from a garage on Vincennes

Avenue in the Chicago suburb of Rock Island Illinois assisted by a young

mechanic named Ray Nichels.

From 1948 through 1950 Pritchard and Tuffanelli entered

Kurtis-Kraft 2000 upright dirt cars in the Indianapolis 500-mile race, but for

the 1950 running of the International Classic, the team entered their new Emil

Diedt built front wheel drive chassis dubbed the ‘Tuffanelli-Derrico Special’.

The second name car on the car was one of Carmine’s alleged underworld business

associates, Jimmy Derrico, who became part-owner of the ¼-mile Raceway Park in

Blue Island in 1952.

For Tuffanelli’ s car Diedt make extensive use of aluminum

including the oil and fuel tanks to make the new front wheel drive car 350

pounds lighter than previous versions. For the driver of the new maroon and

gold Diedt creation for the 1951 ‘500’ Pritchard and Tuffanelli selected their

1950 driver, the mustachioed California midget racing standout Ronald “Mack”

Hellings. Mack originally a motorcycle racer

came up through the URA midget ranks with such future Indianapolis stars as

Bill Vukovich and Sam Hanks and was crowned the 1948 champion of the URA ‘Blue’

Circuit for non-Offenhauser powered machines.

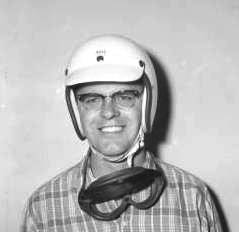

Mack Hellings official IMS head shot

Hellings graduated to championship cars during 1948 and

drove for two seasons for the Los Angeles–based Don Lee racing team before he

jumped to the “Tuffy’s Offy” team for 1950 and he scored five top ten finishes

in nine starts in a K-K 2000 during the 1950 AAA (American Automobile Association)

racing season . When not racing,

Hellings ran an automotive and motorcycle speed shop first located in North

Hollywood and later Burbank California

Helling's company logo

At Indianapolis in 1951, two days before the first weekend of time trials, the ‘Tuffanelli-Derrico Special’ lost a camshaft bearing. On the third day of time trials,

Hellings could only record a four-lap average speed of 123.925 MPH, which held up

although his speed was nearly seven-and- a-half miles per hour slower than the

next slowest qualifier. On race day, Hellings and the new Diedt creation started from the middle of the eight row, but only

completed eighteen laps before the car was retired with a broken piston in the

270-cubic inch Offenhauser engine.

Hellings did not get a second chance to drive the ‘Tuffanelli-Derrico

Special’ at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. On Sunday, November 11 1951, Hellings, fellow

URA racer and engine builder Bob Baker, and URA photographer George “Lee”

Harvey left Brackett Field near LaVerne in a rented plane piloted by Robert

Harris. The quartet were headed north for the ‘Bay Meadows 150’ the final 1951

season championship car race scheduled for that evening at Bay Meadows race

track in San Mateo.

A typical Piper Pacer

The cream-colored single-engine Piper PA-20 Pacer tail number N74568K

was overdue for their mid-day fuel stop in Fresno and after the plane failed to

arrive overnight, search parties were dispatched. On November 15 the wreckage

of the plane and the four deceased passengers was found near the 4000-foot

elevation on the south slope of the Tehachapi Mountains near Gorman California.

Contemporary legend has it that Tuffanelli was so devastated

over Hellings’ death that the car never raced again but the ‘Tuffanelli-Derrico Special’ was

entered for the 1952 Indianapolis ‘500.’ The 1951 driver was Chicago journeyman

midget racer Danny Kladis (sometimes spelled Cladis) who had started racing ‘big cars’ before World War Two.

Kladis was the Mississippi Valley Midget

Racing Association (MVMRA) driving champion three consecutive seasons from 1946

through 1948. Despite his Hall of Fame midget career, Danny experienced tough times

at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, and only qualified for the ‘500’ once in seven years of trying.

It is unclear whether Kladis made a qualifying attempt after he spun the car out of turn two on May 15, and the ‘Tuffanelli-Derrico Special’ never appeared again for competition at

the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. The beautiful #19 Emil Diedt-built ‘Tuffanelli-Derrico

Special’ on display at the World of Speed museum appeared to be in original

unrestored condition sporting its striking trademark gold-leaf nose scallop and

numbers outlined in red pinstriping.

Although they scored three consecutive 500-mile race

victories and three runner-up finishes in four years, the reign of the Emil Diedt

built front drive race cars at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway was over after

just five years. With the early

retirement of the ‘Blue Crown Special’ driven by Tony Bettenhausen from the

1952 ‘500,’ the front wheel drive concept was replaced by the next generation

of Indianapolis race cars, the lighter weight “roadsters.”

The World of Speed

museum located at 27490 SW 95th Avenue in Wilsonville Oregon will feature their

“Celebration of the 100th running of the Indianapolis 500-mile race” exhibit through

April 2017.