The construction

of Phoenix International Raceway

courtesy of PIR Inc.

Recently, the

author browed the history section of the Phoenix International Raceway 50th

anniversary media guide which was published in 2014. Some of the events and

dates listed are approximately correct, such as the completion of the

construction of the track in 1964, but the guide contains several incorrect

statements.

Historic inaccuracies are not unusual with corporate owned entities

and the purpose of this article and those to follow in the coming days is to accurately re-trace the early history of

Phoenix International Raceway (PIR) including and through period during which

car manufacturer Malcolm Bricklin owned the Phoenix track and renamed it

“FasTrack International Raceway.”

The creation of PIR

On the last

day of July 1963, the local planning commission approved the plans submitted by

Scottsdale developer Richard P “Dick” Hogue to build a road racing course and

dragstrip. The 314-acre parcel southwest of Phoenix near the city of Avondale

was laid out in a natural amphitheater adjacent to Estrella Mountain Park on

the east and bounded on the north by the dry creek bed of the Salt River. The planning commission then passed Hogue’s

July 1 proposal onto the Maricopa County Board of Supervisors for final

approval.

Hogue and his

wife Nancy as well as his partner Templeton (Tony) Briggs Jr. all resided in

the affluent Phoenix suburb of Scottsdale. Hogue, a housing and real estate

developer, tackled the created of the new raceway following the completion of

his 62-unit Holiday Apartments project at 511 East Culver Street in December

1962. Both Hogue and his partner Briggs

were accomplished amateur sports car racers who wanted to build a permanent

road course in Phoenix as until then the area sports car races were held on

abandoned airstrips or parking lots.

Briggs had

won the 1957 SCCA G production national championship behind the wheel of his

own Alfa Romeo Giulietta Veloce. Hogue raced in Sports Car Club of America

(SCCA) events beginning in 1957, as he progressed from a Volkswagen Karmen Ghia

to an AC ‘Ace,’ and then in 1959 he drove several races in Cincinnatian John

Quackenbush’s 4-cylinder Ferrari 500 Testa Rossa Spyder. After Quackenbush sold

his Ferrari, Hogue bought and raced his own Porsche 718 RSK and Cooper Monaco,

and in 1964 he owned a Ford-powered Lotus 23B formerly driven by Jimmy

Clark.

The reader

might ask how these two men, Hogue and Briggs, managed to fund the nearly one

million dollars needed for the land purchase and facility construction of

Phoenix International Raceway. The answer was family money - Tony Briggs’ father

was a Scottsdale real estate investor and owner of a Phoenix advertising agency

while Nancy Hogue’s family owned of one of the nation’s premier corrugated box

manufacturers, the Kieckhefer Container Company. Nancy had grown up in a huge

home in Milwaukee which overlooked Bradford Beach on the west shore of Lake

Michigan and her uncle William Kieckhefer was one of the wealthiest men in

America, with an estimated net of worth between 75 and 100 million dollars.

The Maricopa

County Board of Supervisors issued a Special Use Permit for PIR on August 26

1963 and by the date of the official groundbreaking on September 19 1963,

construction was already well underway as described by the Arizona

Republic’s sports editor Frank Gianelli. “It’s gratifying to walk in on a

groundbreaking and find construction already underway. Generally at such

occasions, there's the mockery of somebody leaning on a shovel, a flash of

architect's renderings, and a great volume of promises,” wrote Gianelli, “No

such conditions prevailed yesterday, though - when Phoenix International

Raceway had starting ceremonies on the $500,000 speed site south of Avondale,

great chugging earth movers have already have humped up the landscape and

gouged out the route for the mile closed oval.” James V. Peterson, of

Scottsdale with “paving experience that includes the Milwaukee championship

mile oval,” was introduced as the man in charge of all track construction.

The last years of

racing at the Fairgrounds

The one-mile

“dogleg” oval for which PIR became renowned was not included in Hogue’s

original plans, but added at the suggestion of famed Southern California racing

promoter and USAC Board member Joshua Clay “JC” Agajanian as USAC about to lose

its Arizona venue. The American

Automobile Association (AAA) and it successor organization, the United States

Auto Club (USAC) had staged championship car races on the one-mile dirt oval at

the Arizona State Fairgrounds with various promoters for fourteen years, but

the seven-member Arizona State Fair Commission had voted to end automobile

racing on the one-mile dirt oval at the Fairgrounds after November 1963.

The future of

auto racing on the Fairgrounds one-mile dirt oval had been trouble for several

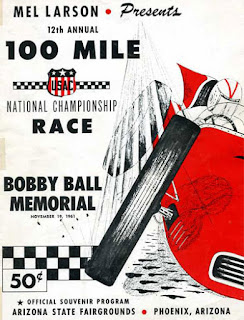

years prior to 1963. Track conditions were bad during the 1961 Bobby Ball

Memorial promoted by Mel Larson. The track began to break up early, as Ray

Crawford’s car flipped in turn two during time trials and Ray was admitted to

the hospital with back and chest injuries. On lap 41 of the 100-lap race Alvah

‘Al’ Keller’s in Bruce Homeyer’s yellow ‘Konstant Hot Special” which had set

quick time in time trials hit a rut then flipped and rolled six times in the

fourth turn.

After a

single lap under the yellow flag, the race continued until lap 49 when the red

flag was displayed; rescuers untangled the fourth turn chain link fence from

the crushed car and removed Keller’s lifeless body for transport and he was

pronounced dead on arrival at St. Joseph’s Hospital. The track was then

re-worked with a scraper and water truck before the race restarted after an

hour and half delay. On lap 88, Chuck Hulse flipped in turn four and the race

ended with 89 laps completed due to darkness.

After the

race, Rodger Ward told the Associated Press “this is the worst track I’ve ever

run on and I’ve run on a lot of them. I hate to see poor officiating, it makes

me angry. I think the race could be a good one if enough thought and

preparation went into it.” USAC competition director Henry Banks was later

quoted "I was on my way to the starting line to halt the show when the

accident (Keller’s) occurred.” For the

next race, USAC attempted to ensure acceptable track conditions by dictating

the promoter to the Fair Commission, and listed Agajanian as the only certified

promoter for the Arizona mile, but that plan conflicted with the annual public

bidding process for the track rental.

USAC racing

on the Arizona Fairgrounds mile edged closer to oblivion after Elmer George’s

“HOW Special’ went through a chain link fence and injured twenty-three

spectators, two critically, standing in the “overflow section” in front of the

grandstand during the 1962 Bobby Ball Memorial race. Fair Commission Executive

Director Charles Garland was quoted at the time that “the fair commission makes

very little money off auto racing; we kept providing one of two race strictly

out of a sense of obligation to the 25,000 fans. But the future of the Bobby

Ball race will be a topic of discussion in our December meeting.”

Race promoter Mel Martin made the curious

statement after the race to the United Press International (UPI) reporter that

“had the crash wall been stronger it would have flipped the car over and over

into the people,” which would have made for a higher injury toll.

Two days

after the 1962 race the Arizona Republic newspaper published an editorial

entitled “Enough is enough” that called for the abandonment of the auto racing

on the Fairgrounds mile. The Fair Commission later faced $1.2 million in damage

suits filed by spectators who alleged that they were injured due to negligence.

Since the race took place before the Arizona Supreme Court ruled that the fair

commission was not immune from liability, the commission had only required

liability insurance coverage of $300,000 from race promoter Mel Martin. The situation

became worse for the Commission after Martin’s insurance carrier stated that it

had notified promoter Martin in advance of the race that its coverage would not

extend to standing spectators outside the grandstand, a claim Martin disputed.

The fight over racing

at the Fairgrounds

The approval

of the PIR use permit was not without some controversy as while the PIR plans

were being considered during July, the South Phoenix Racing Incorporated a

company operated by promoter Mel Martin and a partner Tom Breen, offered a

proposal to the Arizona State Fair Commission to pave the one-mile Fairgrounds

track in exchange for the right to promote four automobile races at the track

annually for a seven year period.

However,

Phoenix Planning and Zoning Commission Chairman Allyn Watkins recommended that

the commission reject the South Phoenix Racing proposal, and cited neighborhood

objections to racing at the track. Martin then charged that the planning

commission had acted "politically on behalf of private interests. I can't

think of any reason for their action," Martin said, "other than it

was promoted by backers of the Phoenix Raceway."

Watkins, also

a neighbor of the fairgrounds, said Martin's plan seemed "economically

unfeasible" to the zoning commission.

The same day that the Maricopa County Board of Supervisors granted their

approval for the construction of PIR to proceed, Martin’s unsolicited offer to

pave the fairgrounds track was unanimously rejected by the seven Fair

Commission members.

However,

despite the ongoing construction of PIR, the future of auto racing on the

one-mile Arizona State Fairgrounds was not dead as in January 1964 fair

commissioners reconsidered Mel Martin’s revised proposal. Martin’s new proposal

called for a 10-year exclusive lease on the fairground track in return for

Martin's investment of $56,000 in track paving new guard railings and fencing

the dirt oval. Martin's investment was to be written off the company's books at

a rate of $8,000 a year over seven years.

If the commission broke Martin's lease before the end of the seven

years, Martin’s proposal called for the fair commission to reimburse him for

any portion of his investment not yet written off.

Under his

revised proposal Martin would stage at least four USAC-sanctioned races a year

and he offered to pay the Fair Commission either a flat annual track rental of

$16,500 or series of guarantees against receipts: $4,000 guaranteed against

12.5 per cent of ticket receipts, 12 per cent of parking fees and 15 per cent

of program sales.

Martin’s

proposal was curious as USAC had stated in 1963 that JC Agajanian was the only

promoter to whom USAC would issue sanctions for racing on the Arizona State

Fairgrounds oval. The Commission

expressed doubts over Martin’s financial ability of Martin's firm to meet the

rentals and guarantees and required $2 million of “advance” insurance coverage.

Later, the Arizona State Attorney General held that the Fair Commission could

not enter long-term contracts binding on future commission members.

In its early

April 1964 meeting, the Fair Commission voted to raze the 59-year old race

track and replace it with a new game and fish building, a new Indian exhibit

hall, a stage for the annual state fair and a $5.5 million 15,000 seat coliseum

which had been planned since 1962.

Executive Director Garland and other Fair officials said that the

construction of Phoenix International Raceway had rendered the fairground

facility obsolete.

The only remnant of the old mile track is the grandstand. Author photo

Even with the

loss of the old track, Mel Martin and Tom Breen were not done with auto racing

at the Arizona State Fairgrounds as in 1966 the pair promoted the closed

circuit telecast of the Indianapolis 500-mile race at the new Arizona Veterans

Memorial Coliseum. The race broadcast was shown on two 20-by-26 feet screens with

carbon-arc projectors placed on the arena floor.

Clarence Cagle’s role

in PIR

When

Agajanian approached Hogue about adding an oval track to his new racing venue,

Hogue agreed, as long as “Aggie” provided someone to design and oversee the

oval construction. Agajanian enlisted the help of Clarence Cagle who had served

as the track superintendent at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway since 1948.

Clarence Cagle's 1957 Passport photograph

courtesy of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Collection

in the IUPUI University Library Enter for Digital Studies

A native of

Terre Haute Indiana, Cagle worked on the Hulman family farm, Lingen Lodge, as a

teenager in the nineteen thirties, and then went to work in various roles in

Hulman family businesses after he graduated from high school. After he spent 33

months as a driver in the U.S. Army in Europe during World War 2, Cagle

returned to work as a “trouble shooter” for the Clabber Girl Baking Powder

Company. After Anton “Tony” Hulman Junior bought the Indianapolis Motor

Speedway’s from Eddie Rickenbacker, Hulman summoned Cagle to assist Jack

Fortner, the pre-war superintendent of the track grounds to get the facility

ready in time for the 1946 Indianapolis 500-mile race.

An ailing

Fortner retired in 1948 and Cagle became the Speedway’s track superintendent

and then in 1952 a vice-president with the Indianapolis Motor Speedway

Corporation, jobs he held until he retired in August 1977. Cagle and his wife Gladys his former

secretary whom he married in 1963 lived on the Speedway grounds in a small

frame house, originally Carl Fisher's summer cabin with one room and a

fireplace. Cagle’s crowning achievement

in his thirty-year career at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway was the two-year

construction of the “new” IMS Museum building completed in 1974.

A 1959

article in the Terre Haute Tribune related that since Hulman bought the

IMS facility Cagle “has never seen a 500-Mile race, since he remains in his

office behind the Grandstand ‘D’ throughout the running of the race in order to

be available at all times to care for any emergencies or problems arising which

may require his assistance.”

Cagle

considered America’s “go to” expert on

race track construction and paving, initially could not fit the layout of a

one-mile oval inside the Phoenix road course, but the addition of the

characteristic “dog leg” off the oval’s second turn made it fit. Cagle remained

involved with Phoenix International Raceway for many years, as he supervised

the oval’s resurfacing in 1985 after the track’s deteriorated condition due to

flooding forced the cancellation of the March “Dana Jimmy Bryan 150” race.

Cagle again supervised the resurfacing of the PIR oval in August 1993.

In our next installment,

we’ll examine the history Phoenix International Raceway after it opened for

racing.

Advertising Firms in Tucson , for marketers, has long been a fundamental resource for fully reaching your consumer potential and, with the launch of the Apple App Store in 2008, mobile apps gave consumers an infinitely greater number of uses for their mobile devices. This simultaneously created an even greater need for more mobile-based advertising and today, mobile advertising has become the fastest growing format in all of digital advertising. For more details: http://www.movement.agency/

ReplyDelete