Lloyd Ruby’s 1966 airplane crash

The author has a long-standing interest in race

car drivers and their fascination with airplanes and flying, and recently found

a reference to Lloyd Ruby’s short-lived flying career. This article adds another chapter to the author's series of

articles on racers and airplanes.

A Beech Bonanza similar to Lloyd Ruby's

During 1966, Lloyd Ruby purchased a Beech B35 Bonanza tail

number N5201C from fellow USAC (United States Auto Club) championship racer

Bobby Unser, who had purchased a twin-engine Beech 95 Travel Air. On the morning of June 4, 1966, Ruby and his

three passengers departed in the Bonanza from the Speedway Airport, a small

airfield located northeast of the intersection of West 21st Street &

Griswold Road South of I-74 near the town of Avon, Indiana. The passengers on

board with Ruby that day were Ruby’s chief mechanic Dave Laycock, fellow USAC driver

Bill Cheesbourg, and Harold ‘Tex’ McCullough, identified in press reports as a

friend of Ruby’s from Hondo, Texas.

Lloyd Ruby waits patiently on pit lane during practice for the 1966 Indianapolis 500 as Dave Laycock makes adjustments to the Ford engine. Photo courtesy of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Collection of the IUPUI University Library center for Digital Studies.

Just five days earlier, Ruby, a 38-year old veteran racer

from Wichita Falls Texas led the first laps in his seven years of competition at

the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. Ruby led the 1966 Indianapolis 500-mile race

on three occasions for a total of 68 laps, before his Bardahl Eagle had retired

with a broken camshaft stud in the 255 cubic inch quad-cam Ford engine.

Ruby and the Ford GT40 in action at the 1966 Daytona 24 hour race. Photo from author's files.

Despite the Indianapolis disappointment (the first of many

to come) Ruby was having a spectacular 1966 season, as he and his English

teammate Ken Miles had won the 24-hour sport car races at Daytona International

Speedway driving a 427-cubic inch powered Ford GT

40 Mark II and the 12 hours of Sebring in a similarly powered GT40 X-1 roadster. Hopes were high for a victory at the

24-hour race at LeMans France on June 19, so that the team of Ruby, Miles and

Ford could claim a historic same-year sweep of the three major sports car endurance

races.

Bill Cheesbourg, long-time friend of Ruby’s had first come

to the Indianapolis Motor Speedway as a rookie in 1956 but only started six

Indianapolis 500-mile races in his career, the last being in 1965. During the month of May 1966, Bill had driven

two entries, neither of which had any legitimate chance of making the starting

field - the Jack Adams Special, an Epperly lay-down roadster fitted with a gas

turbine engine, and former Northern California midget racer Al Stein’s

Valvoline-sponsored twin-engine powered creation, which had a modified Porsche

911 engine at each of the car to provide power to each axle.

Dave Laycock, at age 27, USAC’s youngest chief mechanic had

started in USAC championship racing in 1957 right out of high school as a

helper to “Horsepower” Herb Porter on the supercharged Offenhauser powered Roger

Wolcott-owned entry. By 1960, Laycock was a chief mechanic in his own right with

the team owned by Marion Indiana glass heir Bill Forbes, and first met Ruby

when Lloyd drove for the Forbes team in 1964; the pair had worked together ever since.

Bob Laycock in his office in 1974.

Photo courtesy of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Collection of the IUPUI University Library center for Digital Studies.

Laycock came from a racing family, as his grandfather, C.P.

Laycock worked as a mechanic for the Stutz racing team at the Indianapolis

Motor Speedway in the early days. Dave’s father, James Robert, known as “Bob”

attended the 1915 Indianapolis 500-mile race as an infant, and as of 1966 Bob

had not missed attending a single 500-mile race, a string that would continue unbroken

until 1993. Bob, whose regular career

was with the US postal service, worked during the month of May at the

Indianapolis Motor Speedway in a variety of roles beginning in 1949 that

included timing and scoring, registration and finally the press office.

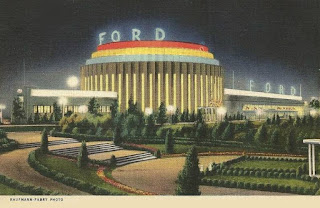

Gaylord "Snappy" Ford in 1939

Photo courtesy of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Collection of the IUPUI University Library center for Digital Studies.

Much of Bob Laycock’s early career at the Speedway was spent

as an assistant to Gaylord ‘Snappy’ Ford, known around the Indianapolis Motor

Speedway as “the man without a title.” ‘Snappy’ born in 1889, first worked at

the Indianapolis Motor Speedway as an assistant to the Chief Starter for the 1920

race and simply never left –Ford did whatever task around the Speedway that was

asked of him.

In the late nineteen thirties ‘Snappy’ became the track’s

chief scorer and served in that role until the outbreak World War 2 forced the

Speedway to close.

‘Snappy’ Ford spent the war years in charge of the Marmon-Herrington Company tank proving grounds, then he returned to work at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway in 1949 at Wilbur Shaw’s request and was in charge of the press office until his death. Legend has it that instead of downplaying the dangers of the Speedway, Ford took novice newsmen on a pace car tour of the 2- ½ mile brick surfaced track and pointed out the gouges in the walls from past fatal crashes.

‘Snappy’ Ford spent the war years in charge of the Marmon-Herrington Company tank proving grounds, then he returned to work at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway in 1949 at Wilbur Shaw’s request and was in charge of the press office until his death. Legend has it that instead of downplaying the dangers of the Speedway, Ford took novice newsmen on a pace car tour of the 2- ½ mile brick surfaced track and pointed out the gouges in the walls from past fatal crashes.

After ‘Snappy’s’ death in January 1953, Laycock assumed

Ford’s duties in the press office also served as the editor of the Indianapolis

‘500’ record book and the USAC rule book, and during the winter worked as a

publicist for the ABA (American Basketball Association) Indianapolis Pacers. After Bob retired from the post office in

1969, he joined the Indianapolis Motor Speedway full time as its historian and

served in that position until 1993. Bob

had two sons in racing besides Dave – Dan, also known as “D.O.” and Bobby who

worked as a scorer for USAC.

The Ruby group’s destination from the Speedway Airport on

Saturday June 4 1966 was the General Mitchell International Airport in Milwaukee

Wisconsin. The group then planned to travel the short distance by car to arrive

at the Wisconsin State Fair Park one-mile oval in time for the start of

practice for the USAC Rex Mays 100-mile race to be run the following day. At

approximately 8:30 AM on that Saturday Bobby Unser in his Beech Travel Air took

off in the downwind direction, rather than into the wind as is typical. Pilot

witnesses on the ground later reported to Indiana State Police troopers that

seconds after take-off, the Travel Air wobbled, but Unser, a pilot since 1958,

applied more power, the twin-engine plane recovered and climbed away from the

airport.

Just after Unser took off, Ruby rolled down the runway for

his take-off, also in the downwind direction. Ruby’s V-tailed single engine

Beech Bonanza reached approximately 100 to 200 feet in altitude, and then fell

into Irene Timmons’ freshly planted corn field approximately ¼ mile northwest

of the airport. Eyewitnesses that included Henry Goebel an architect and

experienced pilot, and flight instructors Stan Leonard and William Lewis stated

that the Bonanza had stalled. When rescuers arrived at the crash scene a few

moments later, they found all four men outside of the severely damaged

Beechcraft.

Lloyd Ruby suffered the most severe inquires, with

compression vertebrae fractures and multiple cuts on his face which took a

plastic surgeon 48 stitches to close. Laycock also suffered vertebrae

fractures, while Cheesbourg suffered cuts to his scalp, arm and leg. The fourth

passenger, ‘Tex’ McCullough who complained of a bruised chest and abdomen was

treated and released while the other three men were admitted to the Methodist

Hospital under the care of Indianapolis Motor Speedway track physician, Dr.

Thomas Hanna. Ruby and Laycock remained hospitalized for two weeks before they

were released to complete their recoveries at home.

Ruby’s injuries meant that he wouldn’t be able to race at

LeMans, and officials at the Ford Motor Company received more bad news later

that day, after A.J. Foyt crashed his #82 Sheraton-Thompson Lotus-Ford in

practice at Milwaukee and suffered second and third degree burns on his hands,

face and neck.

Jackie Stewart's 1966 rookie Speedway portrait.

Photo courtesy of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Collection of the IUPUI University Library center for Digital Studies.

The news got worse for Ford just a week before LeMans when

another scheduled Ford GT40 team driver, Jackie Stewart, who nearly won the

1966 Indianapolis ‘500’ as rookie, crashed his BRM entry during the rain-soaked

Formula 1 race at the Spa-Francorchamps circuit in Belgium and suffered a

broken shoulder, broken ribs and gasoline contact skin burns.

Ford hurriedly called up three replacements for Ruby, Foyt,

and Stewart. NASCAR Ford stock car

driver Dick Hutcherson as the substitute for Foyt in one of the Holman-Moody

GT40s was paired with sports car and Formula 1 driver Ronnie Bucknum, who had practiced

but did not attempt to qualify for the 1966 Indianapolis ‘500’ in George

Reeves’ Chevrolet V8-powered Lola T80. Australian touring car racer Brian Muir

replaced Stewart, paired with Graham Hill in one of Alan Mann GT40s, and Kiwi

Formula 1 driver Denis Hulme teamed with Ken Miles in the Sebring and Daytona

winning Shelby-American prepared GT40 Mark II.

The finish of the 1966 24 hours of LeMans. Instead of the intended 'dead heat,' GT40 #2 on the left was declared the winner. AP photo.

The fleet of Ford GT40 Mark IIs of course dominated the

later stages of the 1966 LeMans 24-hour race and in an ill-advised publicity

stunt, Ford team managers ordered the two front-running GT40s, scored on the

same lap to cross the finish line together. Ford racing officials believed this

would result in a dead heat, but as the Bruce McLaren and Chris Amon driven

machine had started further back in the starting field, it technically had

traveled further and was declared the winner, which thus cheated Ruby’s friend

Ken Miles out his hoped-for 1966 endurance three-race “clean sweep.”

In addition to the races at Milwaukee and LeMans, Lloyd Ruby

missed two other USAC championship short-oval races held at Langhorne

Pennsylvania and Atlanta Georgia while he recovered from his injuries. Lloyd returned

just fifty days after his aircraft accident to race the All American Racers’

Lotus 38 - Ford in the 150-mile Hoosier Grand Prix held on the Indianapolis

Raceway Park 1.875- mile road course. Ruby

started from the pole position, but never led a lap and spun out the race on

lap 43.

Lloyd Ruby told FAA (Federal Aviation Administration)

accident investigators that on take-off the Beechcraft Bonanza “just wobbled

and started to dive,” while the flight instructor witness Lewis stated that in

his opinion the “race drivers were in a hurry.” As aviation safety expert Max

Trescott told the author “the same approaches that bring them success in the

racing world are not the best practices for safe flying.”

John Lingle's biography of Lloyd Ruby is highly reccomended

The subsequent FAA preliminary accident report faulted Ruby

who only had a total of 55 hours of flight time for three mistakes – inadequate

pre-flight preparation, improper and over-loading of the aircraft, and

selection of the wrong runway relative to the existing wind, all of which

resulted in the aircraft’s failure to obtain flying speed. The FAA suspended

Lloyd’s pilot’s license for six months, but it really didn’t matter, as Ruby had

taken his last flight as a pilot. As he told author John Lingle for his

excellent book Hard Luck Lloyd “I didn’t want to fly anymore anyway,”

and Ruby told Lingle he sold the Beech Bonanza for $12,500, which brought a

close to this little-known part of Lloyd Ruby’s life.